Translation produced and distributed by Herman Meijer Drees

The following is a translation from a transcription, including notations, that was made by H. Van den Bos, which was completed in December 2007, of a hand written letter by Bas L. Vaandrager dated 21 September 1945.

By way of introduction: Letter from Bas L. Vaandrager (1900), major and officer of health of the Royal Dutch Indies Army (KNIL), addressed to his family in the Netherlands.

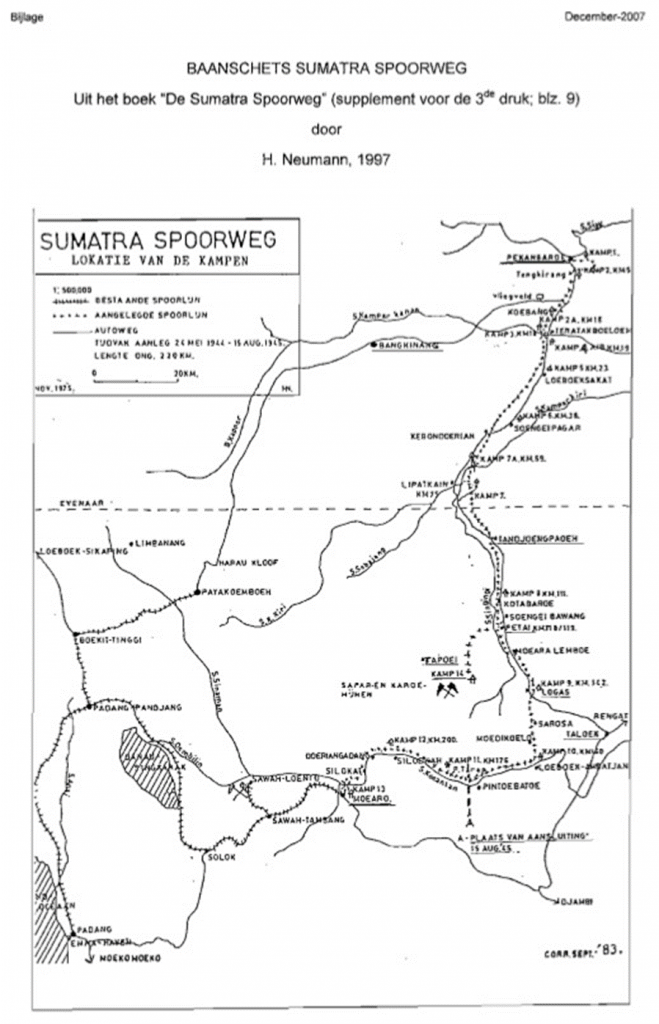

B. L. Vaandrager was detained as a prisoner of war in Union Village (Unie Kampong) in Belawan starting on March 28, 1942; from June 26, 1942, to June 25, 1944, in Glugur (Gloegoer) camp in Medan, North Sumatra; and from the end of July 1944 in POW camps along the infamous Pakanbaru-Muara (Pakanbaroe-Moeara) railway in Middle Sumatra. From March 7, 1945, until the liberation, he was a doctor in Camps 13, 12, and 11 along the railway (ref.: book by H. Neumann and E. Van Witsen, De Sumatra spoorweg [The Sumatra Railway] (Middelie: Studio Pieter Mulier, 1985)). He survived the torpedo attack on the POW transport on the KPM freighter the “Van Waerwijck” on June 26, 1944, in the Strait of Malacca. His wife, Froukje (Frie) Ebes-Vaandrager (1903) and youngest son Joop (1928) were interned in the MV Building, the Mission Complex, and later in “De Boei” (The Shackle) in Padang as of April 7, 1942, and, as last camp, in the Women’s and the Men’s Camps in Bangkinang (Sumatra’s West Coast or SWK) respectively.

During the course of 1941, before WWII broke out in the Pacific, Major Vaandrager was transferred from Magelang (Middle Java) to Padang, SWK’s capital. The family lived there on Vermeulen Kriegerlaan. During WWII, two of their children (son Henk and daughter Co) were being schooled in the Netherlands. The family was brought over with the HMS Glenroy from Padang to Medan in December 1945 and repatriated on board the MS Noordam. The ship arrived in Amsterdam on February 20, 1946.

Note: The original letter was handwritten in pencil, using the spelling of the nineteen thirties, on the stationery of the Australian Red Cross Society in Bangkinang, where, after liberation, Dr. B. L. Vaandrager was assigned to be a “military administrator” based in Pakanbaru. I received a copy of this letter in 1998 from son Joop at the annual reunion of ex-internees from the camps in Padang and Bangkinang. Herman Meijer Drees paid for the translation.

H. Van den Bos, 2007

Bangkinang, September 21, 1945

Dear Everyone,

I thought to give all of you a chronological account of everything that lies behind us and about which none of you ever heard a thing.

Frie and Joop were not allowed to write anyone, and I was bound to certain prescribed texts. From a postcard from Henkie (containing information about becoming a “sinologist,” a message about a lesson from a certain Van der Vonk and being chairpman of a literature club), I understood that you had received 2 cards from me. For the rest, we never received anything for over 3 ½ years.

Henkie’s postcard I sent on to the Internment Camp for women and children in Bangkinang (between Pajakumbuh and Pakanbaru, Middle Sumatra, really Sumatra’s west coast) and it was joyfully received by Mammie, who, along with it immediately knew that I was among the living.

Here and there, I am sure I will occasionally deviate from the intended sequence and maybe the narrative will turn out to be too long and I will have to trim it, but what is missing we will tell of later, only once, though, because the sooner we forget the misery we experienced the better.

Myself, I received a few notes from Frie only for the first year, smuggled in at great risk, then nothing from either her or Joop. Lady Mountbatten personally took our first note to all of you to Colombo. We hope that it reached you quickly.

The letter-writing ban was so strict under the Japs that nothing was allowed to be reported, even about deaths, and the Japs themselves didn’t think it necessary to make any official announcements.

On Java, reliable witnesses saw that several hundred cubic feet of mail from overseas was simply burned, which spared them the difficulty of sorting it.

The group to which I belonged received a Red Cross mailing 1 x, and then it was intended for the English. Luckily the Dutch also got some, and available medicines went to the communal infirmary. The group that left us to build the connecting road from Blangkejeren to Takingeun in Middle Aceh (the so-called “Atjeh Party,” 500 men, 306 Dutch and 194 British and Australian POWs, who had to build the road about 60 miles long from March 8 to mid-September 1944, HvdB) also got a mailing 1 x, including anti-dysentery tablets, among other things, which saved many a life. Such tablets were smuggled from that group to other camps.

Many Red Cross shipments were squandered by the Japs, though, and items were even sold to Inlanders at the pasars [bazaars]!

I will have to write you in odd moments, although my current job has but a few available, because all sorts of things must be put in order to get back to a normal Indies society. Medical supervision is just part of my work. I was sent to Bangkinang as Military Administrator. Keeping up the prewar Civil Administration takes a lot of time because those gentlemen are quick to feel they have been passed over. The point now is rapid evacuation to better housing in a special neighborhood in Padang where for the time being (family) internment will exist until the occupation troops are here and all the Japs have been replaced by our own people.

That a doctor was assigned this job is founded on the incompetence of most of the military higher-ups or on there being ill. This selection came from the side of the Allies because I am one of those who understand and speak English slightly better and who are still young and fit enough to get things moving.

As soon as the Dutch Administration has been set up (the Civil Administration, that is), my best friend from these difficult years, Lieutenant Colonel Bekkers (G. J. Bekkers (1894), promoted 1918 KNIL infantry arm. At the outbreak of WWII, stationed in Kutaraja, Aceh [now Banda Aceh]. After the landing of the Japanese on March 12, 1942, in Kutaraja, Bekkers decided to surrender himself to the Japanese on March 18, because of the poor morale and lack of fighting spirit of the native military and the rebellion of the Acehers. He was the leader of the POW camp in Glugur (Medan) from June 26, 1942 – June 25, 1944, HvdB) will get another chance; he has been “shunted” by our Allied friends because he was not able to get along with the British commander. But I shouldn’t get too caught up in minutiae. Forgive my straying from the topic.

A fresh ex-POW has difficulty knowing what is important and what is not, except where it concerns food. Still, the times that food was an obsession are long past (food was not an obsession, far from it, as long as it was there; what’s worse is talking and thinking about food that isn’t there) and we are even starting to give thanks for some portions. You can see all the citizenry growing, even though at the moment there are still some 50% deficiencies; so Frie, for example, still has symptoms of protein deficiency and pellagra to a slight degree. But then, she weighed 88 lbs and now already weighs 117 lbs (without water build-up) and this makes me expect the best for the future. She is involved in everything having to do with the small household and has never let anything go. Jackie Poppe (B. J. Poppe, 1920, HvdB), a lieutenant’s wife who, together with her little girl Tanneke, was with Frie for 3½ years and has now become part of our family, may not burden herself with housekeeping. Frie’s dream of a “chrome-plated hotel where service will be at her beck and call” is purely theoretical. She would never be able to stand it.

In any event, we will all have to be put to pasture as soon as circumstances are normal again. I live in the men’s camp (in Bangkinang, HvdB), although I hope to be under one roof with the others again in Padang. Joop was with Frie until June 1945, and that was possible only because he still had nothing of a “man” about him because of malnutrition; from that time on, he was spoiled in the doctor’s quarters of the men’s camp and he grew 25 lbs in two months on Jap food, only because of the fact that he wasn’t doing any heavy physical labor anymore, which he did in the women’s camp (chopping trees, hauling logs, cooking, etc.). The reward in kind (a few cups of ketella [cassava] flour) most certainly saved his mother’s life.

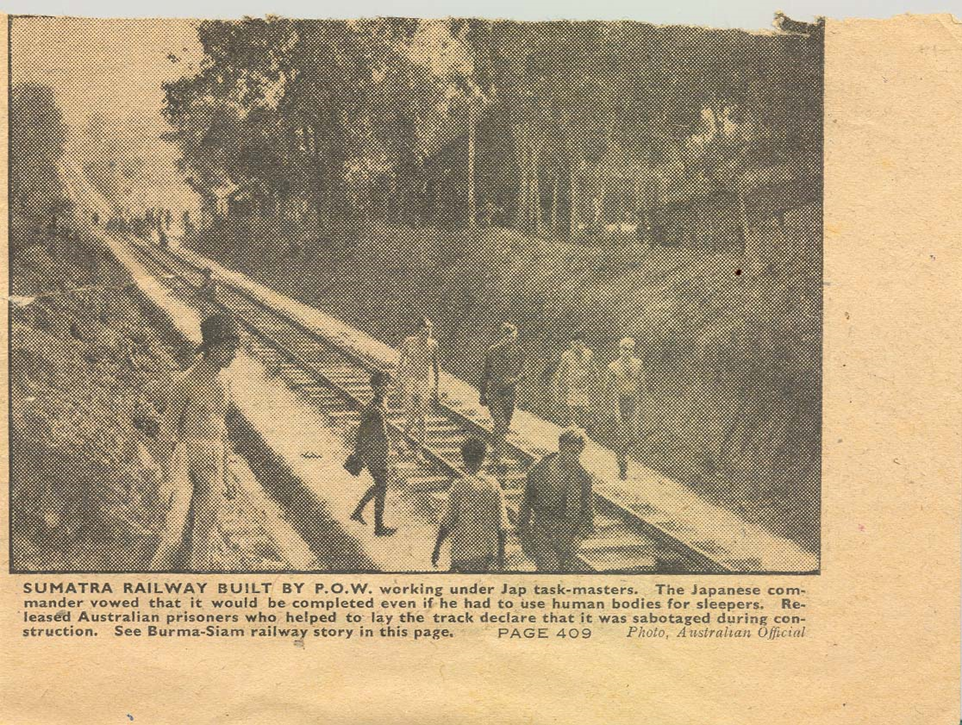

You can all see that it is hard for me to go back to the past. Today, of course, is the only important thing, and the future is still too uncertain to get worked up about. In any event, we did get relieved of any sense of personal property. Money and material things are terribly unimportant after 3½ years of being a pauper, when you longed to be reunited with all those who were dear to you and when even a plate of food was sometimes more important than that. We were a little afraid of the future. What would the first letters from Holland bring us? People are mourning in so many families. Now that news is being exchanged among all the camps, we see more and more women crying. The losses in the Indies are terrible, although not in comparison with the suffering of ’14-’18 reckoned percentage-wise. Teaching will be utterly disrupted for the time being. According to current estimates, 1/7 of the Dutch doctors disappeared. Each sleeper of the little Pakanbaru-Muara rail line (near Sawahlunto) means one dead Javanese coolie. For this work alone, they estimate 30,000 dead. Many thousands were torpedoed during transports from Java to Sumatra.

The native population, too, feels the defeat of Japan to be liberation.

But, let me finally begin.

After being on leave, I mastered the Medical (inspections) Boards work at the Magelang Military Hospital (Middle Java) and afterward, I was employed there for a few months as a garrison medic, even after meanwhile being promoted to major. I had to wait, you see, until the superior officer—doctor of Padang— retired. In Magelang we made it through the awful anguish between the radio report of the bombing of Rotterdam (May 14, 1940, HvdB) and a telegram from the Swedish Consul Hagström, reporting that everyone had been spared. I believe the letter in which Henk (son, HvdB) wrote about the air battles over Waalhaven [military airfield near Rotterdam] was the last one we received. From Co (daughter, HvdB) or from Grandpa Vaandrager we were still able to learn that our children were in Driebergen. Henkie’s postcard was from the end of 1943. I got it in August 1944, and it reached Frie one month before the ceasefire!

August 1941, I became Territorial Doctor of Sumatra’s West Coast (SWK) and Tapanuli (from Sidikalang (west of Lake Toba, HvdB) to Sungaipenuh ± 685 miles, the same distance, I would guess, as from Rotterdam to Warsaw); also Regional Head of the Public Health Service in SWK; commanded 7 Health Officers and 16 Indo Doctors; was on top of this also Head of the Military Hospital in Padang. You will understand that settling into this work environment accompanied by an obvious threat of war meant it was insanely busy. All sorts of exercises and training, military and civilian, LBD [Air-Raid Security Service] (medical) organization, civilian medical war provisions, Red Cross columns, military medical organizations from Padang to Pakanbaru (airfield); when the war became a fact and Singapore fell: transporting away evacuees that washed up on Bengkalis Island and vicinity, with grenade and bomb fragment wounds left untreated for days; after that, also the first misfortunes in our own territory: bombings of Pakanbaru, Emmahaven, and Padang (January 27 and 28, 1942, HvdB) here, two smaller bombs fell about half a mile from our house, but that was it). I was busy and, for example, I would drive back and forth to Pakanbaru in one day. However, Frie had time enough to loathe Padang. In Magelang we had had a pleasant circle of friends. In Padang we really didn’t know anyone, besides officials. The military task in Padang was: prevent access to the Padang Uplands. This became completely insignificant when Singapore started coming under threat. People thought help could be had from Middle Sumatra at the back of the Lion’s City [Singapore]. All the troops, except those from Aceh, fell under General R. T. Overakker *1) since he was Commander of Middle Sumatra. Hoping for Australian reinforcements, according to constantly changing strategy from the headquarters in Bandung, our troops (over 3,000, of which ± 1,500 were Dutchmen) moved back and forth across Middle Sumatra.

Then Singapore fell, and the General Staff knew it was a lost cause. Neither Java nor Sumatra could be held anymore, because just like Malacca, the Dutch Indies were an empty shell (beautifully staged by General Sir Archibald Wavell using enormous staff quarters, motorcades, etc., etc.) and we were playing make-believe, that is we were retaining an appearance, which the Japs themselves are so good at, although they still let themselves be fooled. (The 57-year-old British General Wavell was an accomplished strategist and good army commander charged at the beginning of January 1942 with the ABDA command, an American-British-Dutch-Australian command operation on Java, HvdB)

They landed 30,000 men, for instance, on Sumatra and we kept them busy, according to our orders, as long as possible, namely 3 weeks, without noteworthy losses on our side. On surrendering (the Indonesian military had all run away), they were hopping mad that we were so weak and had no artillery, etc., etc. But I shouldn’t get ahead of myself.

When Java fell, and the General Staff with it, General Overakker was left to attempy it on his own, so we headed to Middle Aceh with the idea of being able to hang on there for some months. I said goodbye to Frie on March 8, 1942. She showed herself to be a good soldier’s wife and didn’t chatter on about the near future, which would bring Jap shock troops into Padang, with all the perils that barbarians bring with them (her experiences are a separate chapter).

So, on to Aceh, thinking that Colonel G. F. V. Gosenson *1) would be covering our back there. No one knew that Aceh had been in full revolt for a month already; the Governor there was a shaky invalid, and Gosenson was starting to go senile. Our plans, therefore, did not end up as we had thought, but the make-believe saved Australia. Had the Japs gone straight to Australia and India, I wouldn’t be sitting here writing this!

In Blangkejeren, I became a prisoner of war on March 28, 1942, and on April 1 we ended up in Belawan in coolie barracks with plugged-up toilets and rice with “sajur looppas” (we would say runny sauce), sometimes with fish in it, completely inedible. En route, half of my belongings had already been stolen by Batak people.

When we were allowed to cook for ourselves, things got better, since we were still getting reasonable basic supplies at that time. On June 25, 1942, we went to Glugur, which is a way house for contract coolies in Medan; hygienic situation fine, food adequate, big library; inspired intellectual life.

They didn’t beat us too much and protests did not yet fall on deaf ears (later on it was wise not to protest because then for some trivial reason or after provocation you would be beaten twice as badly. I was beaten up a total of 3 x for no reason, but thanks to boxing lessons in my youth, I was able to handle it well; only the piece of firewood was nasty. With different guards, beatings increased or decreased. Lots of eardrums ruptured. The officers were not much bothered in Glugur. The field workers had the most trouble. They, and this is another plus, managed to put pipes, grease cups, parts into disarray. They sorted nuts and bolts to be transported to Japan, but better not look under the top layer! They had to set out grass turf on an airfield, it went in upside down. They stole like ravens from all the Jap supply depots. A finer workshop as far as tools went could not have been found in all of Asia. Beautiful industrial craft was produced. It was as easy to have your cup soldered as it was to have your glasses mended. New chrome-plated frames from material they had stripped from cars the minute the Japs weren’t looking.

We were in Medan exactly two years. Judging by what came later and from hearing stories about Java that would make your hair stand on end, we were very lucky during those early days. On June 25, 1944, we were crammed into a KPM [Dutch Royal Parcel Freight Co.] ± 3,000-ton boat, the “Van Waerwijck.” This means that part of the men, ± 1,000 (departed 05-15-1942 for Tavoy, Burma, HvdB), had already been taken out of Belawan, heading to Muimein [Burma]—Burma Road—road construction across the base of Indochina, leading to Bangkok. I stayed behind with the so-called M Group, intended to be advisors to the Japanese economists and other specialists who came for “construction.” The real economists of Japan, those knowledgeable about Deli and Sumatra in general were torpedoed. Their replacements were utter laymen in every area, so it turned into “demolition.” Some in the M Group were placed in companies and offices, but they couldn’t stop the demolition.

All the Japanese services worked at cross-purposes with one another, distribution of raw materials, parts, etc., etc. (food, too!) became incredibly scarce. The group that went to Burma had to combat dysentery, cholera, food shortages, and slept outdoors! Perished in great numbers: coolies 60-80%, English and Australians 40%, Dutch Indies troops 10-15% (well vaccinated!). We received this news in August 1944 in Singapore. We happened to be there by pure chance. The “Van Waerwijck” was sailing as the sole cargo ship in a convoy with three tankers guarded by destroyers. Planes overhead. No lifeboat drill, no lifejackets. We were allowed to go on deck for just a moment in little groups, through the hatches where you sat with your knees to your chin up against each other, to use the washroom, get water, etc. On June 26 at 1:52 p.m., a torpedo ripped into the borderline between the coalbunker and XXXXXX [illegible]. I was just returning from using the washroom on the quarterdeck. At the same moment, the ship was hit broadside. Water came down from the bridge into the cockpit deck. I was wondering where it was coming from because the boat stayed quiet for the rest (one tank had fallen over), and then within two seconds came the second blow, this time into the quarterdeck I had just been on.

The stern with cargo and people shot up and smacked back down. Fifteen feet away from me lay a tornoff arm; the boat heeled sharply, hatch joists started falling around my head; on the other side of the middle hatch the hot water tank fell over and many were badly burned. The so-called hospital on board was partially blown up, the rest empty. “Bastiaan, your time has come,” I thought and jumped overboard. I didn’t even get a scratch from driftwood or sisal floating around (sharp fibers for the gunny sack industry). After I had swum a distance away underwater (I was on the wrong side of the heeling ship and something might fall on my head), I took time to take off my shoes and my riding breeches, etc., etc., and when I looked up again to survey the situation, the first thing I saw was the sleep mate I had lain beside for two years; he was hanging on to a piece of flotsam. A POW had evidently loosened up everything on the bridge that could float. The lifeboat that people had tried to lower had tipped over the falling tackling hit my colleague from Aceh, Lieutenant Colonel Doctor Schrijveschuurder (W. Schrijveschuurder (1896), entered into service on December 16, 1921, as a health officer 2nd class with the KNIL medical service, † June 26, 1944, HvdB). The second field officer—doctor of Sumatra—died in Burma, so I am the only survivor. We pulled two heavily wounded († later anyway) men on that piece of wreckage and just swam toward the coast. A Japanese tanker turned back (one had also been hit and sank immediately; a corvette went up in smoke right before our eyes). The two of us, alternating, pulled that little float, swimming ± 5 hours, which is why we remained in the vicinity of the disaster despite a pretty strong tide.

We were also among the first that were picked up. An even smaller boat returned and picked up those who had drifted far away, but we didn’t know this beforehand. The Japanese sailor seemed just as humane as western seamen tend to be. On board we received all manner of help to the extent it could be given. No bandages. We had 30 wounded on board. For many, the outcome was still unpredictable because they had already been in the water before the second torpedo and so received the full water pressure of the explosion (presumably this generated multiple deaths); the men who spewed blood continued to live, those who had stomach complaints all died, some only after several days.

In Singapore, where we were brought, after a night, a day, and another night on board of that entirely metal tanker, it turned out in the final estimate that of 720 POWs, 180 had disappeared. (The 3,040 gross register tonnage ship “Van Waerwijck,” constructed in 1910, Japanese name “Harukiku Maru,” was sunk at the level of Tandjong Tiram on Sumatra’s east coast on June 26, 1944, at 2:00 p.m. by the English submarine HMS Truculent using two torpedoes. A total of 178 POW’s perished. Three men succeeded in reaching the coast by swimming, HvdB)

I won’t easily forget that tanker, stuffed with practically naked men, broiling hot during the day under the tropical sun, bitterly cold at night. And then in Singapore a stiff hike on bare feet. This was the prelude to poverty. At first, we ate (polished) rice with salt fish from a leaf with our fingers. The vitamin decline was beginning. We made all kinds of items from corrugated iron. The Japs gave us one pair of pants, one shirt, one pair of shoes, and one blanket as our kit, after which after a month’s quarantine we crossed back over to Sumatra on a riverboat that could navigate the Siak (River, HvdB).

In Pakanbaru, we were made available to the Manchukuo Railway Co. (the leaders of this company were picked up as war criminals right after Japan’s capitulation; this ending already gives you an idea of what was awaiting us in Pakanbaru) (what is meant here is the [South] Manchuria Railway Company (MRC), the umbrella organization of which the military organization SARC (Southern Army Railway Corps) is a part. The SARC is responsible for the construction of the railway. The immediate commander in Pakanbaru, Captain Miyasaki Ryohei, was sentenced to death on May 31, 1948, HvdB).

All of our hospital equipment from Medan (even the library) was lost by the wayside and was not replaced, so that medical care in Pakanbaru, still intended to be a basic hospital, couldn’t even be termed medieval. Sheds made of round timber covered with leaves, each person was due ± 28 inches of the sleeping platform (baleh-baleh), no hospital requisites, medications about 1/100 of what was needed, and the important ones (for dysentery, for instance) were entirely lacking. Those who were sick only received half-portions; your own fault, according to the Japs, “then they shouldn’t get sick.”

Against all international regulations, all the officers were put to work, originally to prevent sick military men from being forced to work (a steady number was demanded, regardless of the sick count, so we were never in a position to deliver that number on account of the increasing malaria, dysentery, beriberi, etc.), but later the Japs simply forced the officers to do all sorts of labor.

I uprooted trees right under the window of the Japanese lieutenant doctor. My main task was: looking for vegetables, sometimes “medicinal herbs” too. In the medical service, the Japs tolerated namely only those who weren’t troublesome and for the rest it was typical British favoritism among friends for which the Japs, through a hopelessly shady Dutch interpreter, were always blamed. Well, we’ll get that interpreter someday. With Lieutenant Colonel Bekkers and four others (doctors) we would look in the forest, in the alang-alang [course, tall grassland], and in the ladangs (fields) for edible greens. For 1,200 men in Pakanbaru, we would bring in 130 lbs of greens every day, very welcome, considering the Japs’ supply consisted of nothing but much too old, withered or fermented ketella leaves.

The rice sacks were supposed to hold 220 lbs, but in reality contained 130 – 150 lbs; the rest would have “disappeared” en route; the amounts we were officially supposed to have never reached us; the greater part was sold by the Japanese commissariat for their own ends. For eight months, we walked ten miles every day with a vegetable sack. During the last part of this period, at the beginning of 1945, I was so much at a deficit that my appetite disappeared; the minimal food ration at that time even became too much for me and I became frighteningly skinny, with no symptoms other than “burning hands,” a nerve disorder caused by a lack of vitamin B2 complex, which expresses itself as an objectively cold feel to the hands (or feet) while subjectively they feel fiercely hot, forcing people to stick their extremities in cold water because they can’t sleep.

The first months of 1945 only carcasses came in anymore, every 10-14 days, the bare bones of a buffalo.

On March 3, 1945, I was assigned to form a basic hospital at the other end of the line with five other doctors. This became the rescue for me and my colleagues, because in the work camps, more food was provided. The situation in the Pakanbaru base camp was not to be described by any pen already at that time. Of the 1,200 men, 80, later even 100 per month, died of malnutrition + malaria + dysentery; the total number was stable because there was a constant influx of new sick men from other camps.

The Muaro Camp (= Camp 13, HvdB) near Sawahlunto at the end of the existing railway to Padang I will describe in somewhat greater detail because I was the “official” there and therefore witnessed the Japs’ work method from up close. This information concerns a small group of POWs, although everywhere the Japs seized upon public work projects, similar and even worse situations existed. In the Pakanbaru Camp for the Sick, they didn’t even announce burials anymore, although people there were already too worn down anyway. Bodies were wrapped (usually naked) in a mat and buried that way, a coffin could not be wasted on them; at the graveyard we filled up before the last one, the groundwater was so high that the bodies had to be shoved underwater with sticks in order to be able to close up the pit. The last graveyard was right above the hospital (on the other side of the little culvert that was supposed to provide us with drinking and bathing water and in which the Javanese coolies with intestinal bugs would relieve themselves upstream), some six or eight hundred feet from it.

When I came back from Muaro, recently now, there were already over 500 buried there. Mortality in the civilian camps (in Bangkinang, HvdB) remained surprisingly low, but there was no forced labor there, either, although various men, women, and children worked hard in order to earn a little extra flour. Over ± 12 acres of rubber groves have already been felled by women and children for firewood and to cultivate ketella (= sweet potato) plots. A dam in the river was built by women! But this belongs to Frie’s story.

We’ll go back to Muaro and the other camps for laborers on the railway along the Ombilin, Kuantan, and Siak Rivers, because we would move house as the railway progressed. This meant an ever-worsening of the housing.

On March 7, 1945, we arrived at the island in the Ombilin where Camp VII (according to information from H. Neumann’s book De Sumatra spoorweg (1985), this must have been Camp No. 13, HvdB) had been set up. It took us four days to make the trip from Pakanbaru, partially by train (that trip aroused memories of carnivals: rollercoaster; the rails were laid inexcusably sloppily and any expert would have been overcome with horror and / or sarcasm; derailments are the order of the hour), partially by truck; the steering mechanism of one of these vehicles had been repaired with a piece of wire, and the journey passed along winding roads and along steep cliffs; once we slipped and the container was already hanging over the abyss, its wheels just barely on the edge. That was the umpteenth narrow escape. (According to coffee grounds and the egg and readings, which those in the women’s camp did, I have a very special guardian angel!).

Until the beginning of April we were in the Island Camp. Some poles in the ground, a roof of just enough leaves, and sleeping quarters on two levels for 500 POWs, for each one 24 inches of “living space.” Split bamboo poles to sleep on, stuffed with bedbugs. A clothes-louse plague on top of this; reasonable hygiene was utterly impossible. The infirmary was exactly the same, although one level, into which 30 sick men could be crammed. No hospital requisites. Tables, benches, racks were made of bamboo and stolen wood (the Japs didn’t offer a single board, not even to cover the night latrines; the danger of dysentery was increased unnecessarily this way because we were not allowed to go to the river at night.)

Thank God we got only 10 dysentery cases of which 6 were amoeba dysentery, which last tends to run a less explosive course; but emetine, the remedy of choice, was not to be gotten in all of Sumatra, not even in exchange for watches that the Japs and Koreans were crazy about and that before long would bring in thousands of Jap guilders. Devaluation increased hand over fist as the population caught wind of the fact that the Japs might someday be defeated. The wages and officers’ salaries were nothing when it came to the clandestine purchase of a couple of pisangs [bananas] or an egg now and then. (All the officers gave half their income to the general camp fund for 3 ½ years, making the general kitchen a bit more appetizing; the lower Japs delivered for fancy prices; the Japanese commander didn’t want to have anything to do with canteen matters).

The way to get hold of money was to “make a good sale.” The natives who walked around in tree bark paid hundreds for a piece of cloth or a jacket or a pair of old pants. Contact was strictly forbidden, however, and was severely punished. And yet the whole camp was soon walking around in jute triangles, for with the gradual reduction in food, the necessity of buying extra became more pressing. The Japs never exchanged or supplemented clothing, so all the POWs looked like vagabonds. Those who survived being a prisoner of war largely thank the fact that all the Japs (and particularly the Koreans) were thoroughly corrupt.

It was the intention that not a single westerner would survive. All the measures from higher up, which were even worsened as mortality increased, pointed in this direction. The Japanese captain district commander said it straight out: the more that die the better (the charges against this war criminal have already gone to the International Agency that terminates these cases in short order by hanging).

We received 14 ounces of rice in Muaro initially, a lot of good vegetables (leeks and cabbage), and almost an ounce of meat per day. According to the commissariat, we were entitled to 2 ounces of meat, but our 26 guards took as much of our store as the 500 POWs got, and another part would have disappeared earlier in the baskets of the prostitutes who also stepped up at the distribution point. A complaint to the Japanese lieutenant commander resulted in a heavy beating for the Dutch camp commander, also interpreter, by the [fourier = nonexistent word] in charge. And it didn’t make any difference if we complained our not.

The workers got up before sunrise and came home long after sunset, during the last month sometimes even not until the next morning. They were thus heavily exposed to malaria. Letting an illness run its course to recovery was not permitted by the Japs, so they kept getting relapses, up to 60 and more, we counted. (Myself, I had the first malaria attack of my life on June 30 of this year, very slightly, and so far no relapses.)

When it rained, the practically naked workers (some worked entirely naked!) would return entirely stiffened up after hours on an open freight car, and a new malaria attack would promptly ensue.

At the beginning of April 1945, the river rose about 30 feet and we were washed out of our camp. For hours we stood holding a rope in water up to our chests to bring all of our meager belongings to safety, including the precious store of rice and tapioca flour (we got tapioca pudding in the morning; this stuff used to be supplied to the textile industry to lend a finish to cheap fabrics, and the Dutch housewife loathes the “paste” just in this last form, never mind we who had to eat it. The civilian camps got practically nothing else during the last year!).

We were then settled in Muaro in a wood shed belonging to the Ombilin Coal Mining Company under a sheet metal roof, where even 20 years of experience in the tropics could not deal with the heat: murderously hot!

Once a day we got a half hour to bathe in the river 300 yards away and throw away the trash at the same time.

The latrines, now for daytime use as well, were one squirming mass of myriads of fly larvae. Nothing was allowed to be done about it, even though the dangers were explicitly pointed out numerous times. Those who were sick were assigned to camp duty; those who could stand had to go to the railway. In order to deliver the number that the Japs demanded, under the pressure of the threat to reduce the food and even to seek out people themselves to fill the quota (a risk we couldn’t take), the medical service had to resign ourselves with bleeding hearts to the fact that those who had barely recovered and even those who were sick were assigned to the work groups (of course the less severe cases went first; we couldn’t leave that decision to Nippon, not even to the Nippon Medical Service that turned out to be utterly incompetent; one of our sergeant nurses knows more than a Japanese doctor).

In order to rescue a few people who were sick, Red Cross personnel would go out as railway workers. The rations gradually diminished, more and more people who were sick were kicked out on the railway, the level of health dropped alarmingly, 10% already had symptoms of beriberi and protein deficiency, and this was among the people who were selected (those who were unfit or weak were sent to Pakanbaru, after all; our disease and mortality rates were thus made rosier); there was nobody available anymore for camp hygiene.

I protested in writing to the Japanese lieutenant, camp commander, pointing out that 1/3 of the POWs suffered from chronic malaria, that the daily illness rate for malaria was 120 out of 500, that the treatment was absolutely nil according to the International Malaria Commission of the League of Nations standards, even though quinine bark was provided (which gave people diarrhea), that the meat ration kept diminishing, that the sending of those who were sick on fatigue duty against everyone’s medical conscience, that the Dutch doctors could not accept any liability. The record of this letter was lifted from our archives by the Japanese lieutenant and destroyed when he knew that his cause was lost, thus producing a complete case of self-incrimination!!

By giving a beautiful watch practically as a gift to the Japanese sergeant, we were able to slow down the reduction of food and we even got three vats of coconut oil. The poor nutritional situation made every tiny injury become sores, lots of the infamous “tropical sores” (these necessitated a lot of amputations in Thailand; in our case, the largest were only 4 in2).

Anything that resembled treatment, we couldn’t give. We received 15 rolls of gauze bandage per month for 500, later 800 men. So rags were used, and sackcloth. After use, it would all be boiled up for the next patient. This boiling was done in a can that also had to be used for preparing quinine tonic and other medicinal brews.

In the next camp (so-called Km 20) (this is Camp No. 12, 20 km from Muaro, HvdB): even more people who were sick had to be put to work. That camp was even more primitive, more crowded, and yet shelter for another 300 men had to be found in two days.

The terribly leaking roof was extended down to the ground thereby forming two new barracks alongside the original two-story barracks. In these dog hutches, we had 20 inches of “living space,” dark and damp and crammed with ineradicable vermin that then disturbed the little sleep that people got.

When the 300 so-called “strong men” arrived, a work group of 540 was demanded, although we could find only 400 for whom the risk wasn’t all too great. Of the 300 selected men, 10 had beriberi, 3 pellagra, 6 had optical nerve infection (with impending blindness), 31 were debilitated, 9 had a hernia, 23 had tropical sores, 64 manifestly had malaria, 1 was over 60, and 12 were over 50.

Our interpreter protested daily, I would write the numbers down, emphasized that almost all 800 men were borderline deficiencies and that a greater number of workers meant a threat to life for many. Nothing helped. The railway had to be finished. The order even came that the rations were to be: 14 ounces of rice per day for workers, 11 ounces for “inside” workers, and 7 ounces for those who were ill. This was quite simply murder. We just took more out of the store and did a good job of duping the Japs in hopes of a timely ending to the misery.

Moved to Km 36 (this is Camp No. 11, HvdB), to an even more primitive camp (many had to sleep on the bare ground!); work hours were extended. No time for bathing, washing, drying clothes, or being sick. The men slept under the rail or sleeper they were lugging; in pitch-black night, they worked over 60-foot-deep ravines on narrow bridges; one fell and broke the base of his skull, †, another’s arm was ridden off (the operation took place in the open air on a table consisting of some lathes laid over wooden crates, instruments and bandages boiled in a saucepan).

August 15, 1945, the railway had to be finished (later, we heard that this was related to the Manila Conference), and from August 13-15, the workers slept one in 36 hours. And the line was finished. In Camp Km 20, we had to select 150 weak men to go to the Pakanbaru Camp for the Sick. We got 150 back; five of them died in the first week; this illustrates the standard of what was supposedly still fit. We buried 25 of our group in five months, but we hadn’t actually had it “so very bad” and by far the majority consisted of Indo boys who turned out to be much, much more resistant to poverty in the tropics than the totoks [Chinese immigrants].

On August 16, our circumstances changed as if by magic. Reasonably fit were, at that point, still 20% of the Brits and Australians, and 40-50% of the Dutch, but the numbers that cover all the POWs are of course much, much lower. No one is 100%. We are improving by leaps and bounds now the misery is over.

The third week of August brought an overabundance of food. Suddenly there was plenty of meat, we received medications that supposedly never used to be available, received plenty of bandages; precious items were returned; Koreans came to tell us that they were so sorry that they had beaten us. Then I knew the end of the nightmare had come, although officially we still knew nothing. No one was still in a state to believe anything anyway. “We’ll have to see it first,” was the opinion of most. And we saw.

When we were once again being taken away somewhere (Camp No. 11 was not removed until August 31, 1945; nothing was known about the capitulation! HvdB), we passed the so-called Logas Camp (this is Camp No. 9, at Km 142, HvdB). Standing there were 1,200 cheering ex-POWs wearing our colors on their chests.

Even before the train had come to a halt there, I had a note from Frie pressed into my hands!! New clothes for everyone were there. This was suddenly too much for our group; first here, then there, a big guy would be blubbering, and at the dignified raising of our flag, we began blubbering all over again.

Up to Pakanbaru, we sat for 34 hours in an open baggage car. But that didn’t count for us. It was over. Over!! After a day in the old Camp for the Sick (Camp No. 2, HvdB), a bivouac was set up for officers and we were practically interned there again.

The Japs were (and still are) responsible for feeding and taking care of us and for keeping order and calm. Freedom of movement where there were still a lot of Japs was less desirable. All the organization was in English hands as before (Dutch officers are always too low in rank in comparison with the much younger Anglo-Saxons and that results in all sorts of problems. When the hospital ship Orange sailed off, it turned out to be necessary to temporarily give all the doctors on board a higher rank or they would have no say overseas.).

We are still now under the Allied Command, waiting for Dutch troops and Dutch Administration. This is how it was possible that even the oldest Dutch troop officer, Lieutenant Colonel G. J. Bekkers, was hidden away in the officer’s camp. A few days ago, the English Lieutenant Colonel who has until now been the boss (still a youthful fellow) left, but his successor was an English captain, and there is nothing to be done about that as long as we aren’t our own bosses. There are more authorities, however. Major Jacobs, a South African, fell out of the sky in Medan to come organize here; he did see, somewhat to his surprise, that we weren’t completely crazy and that things were running here.

(The South African Major G. F. Jacobs, Royal Marines, jumped out over the Medan airfield with four men, all belonging to the “Arrest Party.” Ref.: Opdracht Sumatra—het korps Insulinde 1942-1946 [Assignment Sumatra: The Insulinde Corps 1942-1946], book by J. Th. A. De Man, 1987, De Haan Publishers. G. F. Jacobs published his experiences in 1965 in his book Prelude to the Monsoon. This book, at least the first part, is unfortunately founded on fiction and the experiences and witness of others. The book was translated in 1982 under the title “Een wedloop met de moesson” [A Race against the Monsoon], HvdB)

Subsequently five guys (actually seven men, HvdB) fell out of the sky in Bangkinang: Major Langley, Captain Dr. Clark, First Lieutenant Ledeboer and two radio-telegraphists + sets; intended as localized pressure on the Japs who had to take care of the civilian camps.

(The “five guys” belonged to the “Sympathy Party” which consisted of 3 Englishmen and 4 Dutchmen from the Insulinde Corps in Ceylon. This RAPWI [Recovery of Allied Prisoners of War and Internees] group parachuted over the men’s camp in Bangkinang on September 1945. This group had been flown over by the “Liberator” by naval pilots from Squadron 321, operating from Ceylon, with a flying time of 10 hours. The group consisted of the following members: Major C. A. Langley (Royal Scots Fusiliers), Captain D. H. Clark (health officer), Sgt. T. A. Atherton (medical sergeant), and the Dutchmen KNIL First Lieutenant F. Ledeboer, KNIL Sgt. J. Th. A. De Man, KNIL Sgt. A. Van Onselen, and the KNIL “Chinese” telegraphist Tan Cheng Eng, HvdB)

Ledeboer talked about Holland. The story about the press-gangs gave us the scare of our lives. It was a great effort to trust that Henkie had stayed out of it. He talked of the ravaging of our dear little country and about the underground actions. Later, we heard more about that from Captain Albers, just from the Netherlands, coordinator of the work of reconstructing the government of the Dutch Indies out of Brisbane, Australia, where 800 men were supposedly at the ready. Only ± 25 have been let loose on Sumatra. They will also organize the import of all the items that are necessary for the normal life of a European. For the time being, we will undoubtedly live very simply, although in Holland things aren’t all they should be, either. The main thing is that the three of us are together again and that we will soon have contact again with Holland. You will all have a lot to tell us as well. I am counting on it that you all will write at least as extensively as I am doing now. But I have strayed from my topic again.

Having nothing to do in Pakanbaru, with Frie 33 miles away, did not sit well with me. I asked to talk with Mr. Idenburg. Esq. at headquarters, who as a civilian with the rank of soldier had been stuck in a military camp in order to better keep an eye on him, but the man who was doing that left and his successor knew of nothing. Thus, he came to Sumatra with the workers. Upon liberation, his rank was suddenly reconfigured to that of major general.

(Dr. P. J. A. Idenburg, former head of the cabinet of A. W. L. Tjarda van Starkenborgh Stachouwer (1888), who had been installed since September 17, 1936, as Governor General of the Dutch Indies. After the war, P. J. A. Idenburg was supposed to fulfill the function of Director General of General Affairs under H. J. Van Mook, HvdB)

I made it clear to him that my task as the former head of the DvG (= Health Service, HvdB) in Sumatra’s West Coast lay in Bangkinang with the interned civilians who had minimal medical care and who in addition needed to be evacuated soon, for which medical and other services had to be set up in Padang or somewhere else, whereby the military should step forward as long as the Administration wasn’t sitting pretty yet. This was a completely new point of view for him, at least that was my impression. His hands, of course, were tied, as he said, but the next morning the “Vaandrager Hospital” was formed and several days later we left. Transportation is still the hardest thing. It is a devil of a job prying something away from the Japs. Now, however, Major Langley is pounding his fist on the table and things are a bit easier, although not yet ideal.

I had barely jumped out of the car in Bangkinang when Frie and Joop flung their arms around my neck. These are moments that are trivialized by any description. I already wrote about how I encountered the two of them. Even though Frie had prepared me, the sight of her still shocked me. She escaped by only a hair. However, I can assure you that the damage will not be permanent. We’ll make a blossoming woman of her once again, at least if we receive good news from Holland.

Except for the fact that food has now very significantly increased and is more balanced when it comes, all matter of things keep dropping from the sky, all sorts of cans, plenty of milk for the sick and for children, vitamin tablets, clothing, toilet articles, writing paper (as you see), except distributing it is very difficult. In order to satisfy everyone, all the packages intended for an individual have to be divided among a large number of people and everyone has learned through misery to look askance at the neighbor’s portion. There was a time that a few grains of rice were important, and people have not yet rid themselves of that attitude.

Inside these camps there is also the population of the infamous outskirts of Padang, with all the negative characteristics of the suspicious, conniving little Indo and of the shrewd, calculating, lazy Minangkabauer. This makes the internal camp administration very hard. They steal like ravens. You can hardly get any of them to do work for the common good. I am now threatening militarization with the associated disciplinary regulations. Will not hesitate to lock them up if necessary. Better, of course, is to convince them and stepby-step policies. The people are only just free and it is not psychologically fair to tighten up the reins again right away. They had enough suffering at the hands of the Japs.

Now the Japanese doctors are buttering us up. They should have thought sooner of their duty to act according to the high standards of the profession. At every opportunity, I will tell them how the Japanese medical service failed. It is time that those gentlemen “lost face.”

In Japan, according to the latest news, it’s starting to look this way, too. The punishment will be dire, but not dire enough to avenge all our murdered comrades, wives, and children. Exterminating the Japs will not garner any sympathy from anyone in the Dutch Indies. For now, it’s best if they don’t show themselves outside their own country. The manner in which the military police (MP = Kempeitai, HvdB) here took action against so-called conspiracies, utter fiction by the way, defies all description. Many of the Dutch opted for suicide rather than a second “interrogation.” The refined torture that the Asian mind can manage to concoct makes writing about it suffering, let alone what they felt, those who underwent it. Entire groups were exterminated, including practically the entire Ombilin Company leadership (Ombilin Coal Company in Sawahlunto, SWK, HvdB), despite the many who were mutilated for life and those who starved to death in prisons. General Overakker, Colonel Gosenson, and still a few others have been executed *1).

A few doctors and the late Lieutenant Colonel W. Schijveschuurder, among others, only barely escaped sentencing for fictional crimes. I had been in the Region only a few months, so my name was never mentioned purely by accident by those who, under the exigencies of torture, fabricated the names of their “co-conspirators.”

I’ve been lucky these 3 ½ years. During that time, all the inhabitants of the Dutch Indies had to face for better or worse an indescribable number of oppressive and harmful factors. They fought to retain their health and strength of spirit, and right after liberation, a miraculous resilience was revealed everywhere, Dutch toughness was revealed. And now, from the outside world, from agencies working side by side, all manner of well-intentioned assistance for the rebuilding of the country, for unifying separated families, etc., is coming in.

The guidelines and orders from Allied leaders in a region still governed by the Japs do not take into account one iota the very different colonial relationships we have. We are continually fighting insane evacuation plans. Prompt and better housing is indeed urgently needed. What has been forced on us thus far has aroused nothing but dissatisfaction and worry. There are too many authorities.

Singapore is also an utter zoo. The instructions from those who are coming to help from outside show that it is assumed that ¾ of those who live in the Dutch Indies are nut cases. We may have become somewhat sensitive, but it is crazy that no one ever thought that there are still liberated civilians and military to be found who could perform constructive work or provide constructive advice about Indies relationships that they know inside and out.

Indenburg has not yet received a single assignment from the Dutch Government, is officially a zero, as are Governors, Residents, etc. Unofficially he is attempting to influence the English leadership. But if Padangers are going to be brought to Medan, with a loss of goods that are absolutely essential but that are not allowed to be transported by plane, with a chance of arriving in Padang without sacks of loot, kitchenware, and so forth, they will flatly refuse to do so, regardless of their “good intentions.” We are in the position of overly doted-on monkey young.

Before I forget: I mean for this letter to be circulated among the entire family. Frie meanwhile (we’re writing now on September 26) weighs over 123 lbs. She is growing in spurts! Last night was the first dance evening that has been organized, with the military band from Pakanbaru, and there were lots of guests. The new generation thought it was “swell,” while the older ones felt they could do without such entertainment for a long while yet.

There are so many things that count for so much more. We have had lots and lots of time to ponder things. For the first two years, I was able to read and study a lot, things for which there was never any time before. That, on the other hand, was one small benefit over and against all the drawbacks. Wherever they could, the Japs tried to humiliate us, but they always felt that this entailed as much humiliation as in the sting of a scorpion. The Japs were aware everywhere and every moment of their inferiority.

As the Japanese administration weakens, the poison of the nationalistic native movement is now dripping (including Sukarno on Java, with dreams of Indonesia Merdeka [Free and Independent Indonesia]).

The longer the Allied occupation lasts, the more troubled the political relationships will become. “Something grand” can honestly still be done here. The younger generation will have to teach the older one a new spirit. The “old men” failed miserably and are still failing. I think enough’s enough.

This will be the last page. We find it incomprehensible that there are no regular communications with Holland yet. Not even over the radio. The Dutch POWs in Bangkok and Saigon still have no communications with their relations in the Dutch Indies. An OvG (= health officer, HvdB) has arrived here to exchange lists, but this is a private initiative.

All the Japanese photos and films of camps in East Asia are fake, deception, everything was carefully staged and rehearsed; the so-called memorial for the Allied victims was made of bamboo and cotton and was dismantled after the shots of laying wreaths. Transport of the sick appears ideal in the western sense on film, but 60 feet further on, those sick people were kicked off the stretchers. Those wounded in the torpedo attack had to be carried by hand to big tin buckets of cars that had stood in the tropical sun for hours. For the wounded Japs, there were stretchers and ambulances. Oh well, “schwamm d’r über” [“let’s forget about it” in misspelled German].

They are being placed on islands in Great East, and Allied guards are probably not toying with them. All of a sudden after the capitulation, Japs of every stripe were wearing the emblem of Geneva, which they had trampled on and refused to recognize before. We won’t pay any attention to those little armbands. Just recently, our “oldest daughter,” Mrs. Poppe, received a letter from her husband. That brought a lot of joy under the eaves (they live on the second floor. You get “home” by way of vertical steps going up 6 feet, 65 ft2 for initially four, then when Joop was away three persons. There is a kitchen nook, seating on the mattresses rolled up during the day with a Sumba kain (= Malaysian, cloth, fabric, HvdB) on them, a little tiny table + 2 benches, one of the two wall mirrors the camp possessed in the corner on a little rack with toilet articles, a mat on the floor, all of it paltry but still cozy, at least a lot homier than any men’s residence ever was.). Hooks have been put into the collar beam to hang buckets from to catch the rainwater leaking through.

Whenever there is company and it starts to rain, Frie will say of herself, “You see? Once a pauper always a pauper.” She had to have a bad root pulled and now has a plump face on one side, but she has no pain there and eats like a horse. She has already custom fit an English uniform for me and so gradually I am beginning to feel “married,” even though the men have to be out of the barracks at 8 o’clock and out of the (women’s) camp at 10 o’clock.

Lunch and dinner I get at the women’s camp where the girls always have some kind of treat over and above the normal central pot that is murder for one’s figure. For the time being, I still have a youthful physique. Joop is as fat as a porpoise, looks very much like me, according to others (kasihan [a pity]) and has the most unruly hair in the world. He cooks and fries fabulously and also does all the buying at the market. People pay with old clothes, packs of cigarettes (that pour in like water), or hundreds of Jap guilders.

A start has already been made on making identity (doubling as ration) cards. The occupation forces will be bringing food along for us for another month. After that, we hope for normal circumstances again through advances to be paid in new legal coin. We need a massive injection of food and goods.

But we long the most for letters from all of you, even though perhaps not everything will be back in order where you are. Where is there no suffering? However, we have faith. We have already known for so long that in our little lives, we will need to accept. May God ensure that everything is well with all of you. Much love, Bas

Notes: *1) On February 9, 1942, Major General R. Th. Overakker (1890, promotion 1912 KNIL infantry arm) landed in Medan from Java with a small staff and was charged with the function of territorial commander of Middle Sumatra. This command encompassed the East Coast, Sumatra’s West Coast, and Tapanuli Residencies, as well as the Bengkalis District (on the Sumatra mainland, with Pakanbaru airfield) of the Riau Residency. Headquarters were situated in Prapat near Lake Toba.

The emphasis of defense was placed on keeping the Emmahaven (Padang) and Sibolga harbors open for connection with Java and overseas, from where reinforcements could be expected. Medan’s harbor (Belawan) had become all but worthless as a result of the Japanese advance in Malacca [southern portion of the Malay Peninsula]. On February 11, the oil installations near Pankalansusu and Pankalanbrandan (about 55 mi north of Medan) were destroyed.

General Overakker received the additional assignment after he arrived to form two battalions that were to serve to reinforce Java (!), causing the already limited number of troops at his disposal to be reduced even further. Due to the great Japanese maritime threat in the Indian Ocean, only one battalion was able to depart. On February 15, General A. E. Percival decided on the capitulation of Singapore. About eighty thousand military of the 18th English Infantry Division, the 8th Australian Division, the 9th and 11th Indies Divisions, and a few British battalions became prisoners of war.

Colonel G. F. V. Gosenson (1888, promotion 1909 KNIL infantry arm; as a captain in Aceh, he was distinguished on November 2, 1927, with the MWO-4 order of knighthood) had been charged since 1936 with the territorial command of Aceh. He was fluent in the language of the Acehers.

After units of the Japanese 25th Army landed in Kutaraja, Idi, and south of Medan on March 12, it was decided to retreat and make a stand in the Alas Valley in the mountains of Southeast Aceh.

General R. Th. Overakker and Colonel G. F. V. Gosenson did not come to a pretty end. Both were taken in mid-July 1942 to Formosa where they were interned in Karenko and Shirakawa Camps together with Allied superior and general officers and Governor General A. W. L. Tjarda van Starkenborgh Stachouwer, the so-called prominent figures belonging to the “Special Party.”

In September 1943, Overakker and Gosenson were brought back to Sumatra, where they were interrogated in Medan and Fort De Kock by the Kempeitai (Japanese military police). The Japanese had made arrests whereby indications were discovered concerning an underground resistance movement. Both were suspected of belonging to those taking the initiative for this organization and sentenced by a so-called court-martial of the Japanese Army in Fort De Kock and executed (read beheaded) on January 9, 1945.

Major General of the Infantry of the Royal Dutch Indies Army R. Th. Overakker received the highest distinction for bravery by posthumous Royal Decree No. 15 of July 25, 1951, as Knight of the 4th Class of the Military Order of William (HvdB).

CONSULTED SOURCES

De Jong, Dr. L. Het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden in de Tweede Wereldoorlog, Deel 11 [The Kingdom of the Netherlands during World War II Volume 11]. The Hague: Dutch Government Publishers, 1984.

De Man, J. Th. A. Opdracht Sumatra, het Korps Insulinde 1942-1946 [Assignment Sumatra: The Insulinde Corps 1942-1946]. Houten: De Haan, Unieboek BV, 1987.

Dutch Department of Defense, General Staff Headquarters, Military Science Department. Nederlands-Indië contra Japan, Deel VI [Dutch Indies against Japan, Volume VI]. The Hague: Staatsdrukkerij en uitgeversbedrijf [Dutch Government Printers and Publishers], 1959.

Dutch Department of War. “Naam- en Ranglijst der Officieren van het Nederlandsche leger en van dat in Nederlandsch-Indië” [List of Names and Ranks of the Officers of the Dutch Army and of That in the Dutch Indies]. 1925: Volume 94. Gorinchem, Netherlands: J. Noorduyn, 1925.

Hovinga, H. Eindstation Pakanbaroe 1943-1945 [Terminal Station Pakanbaru 1943-1945]. Amsterdam: Buijten & Schipperheijn, 1996.

Immerzeel, B. R. and F. Van Esch. Verzet in Nederlands-Indië tegen de Japanse besetting 1942-1945 [Resistance in the Dutch Indies against the Japanese Occupation 1942-1945]. The Hague: SDU Uitgeverij [Publishers], 1993.

Jacobs, G. F. Wedloop met de moesson [A Race against the Monsoon]. Franeker: T. Wever, 1982; Dutch translation. Prelude to the Monsoon. Purnell, 1965 (original edition in English).

Lapré, S. A. Dutch Indies in Brief (1940-1945). Self-published.

Leffelaar, H. L. and E. Van Witsen. Werkers aan de Burmaspoorweg [Worklers on the Burma Railway]. Franeker: T Wever, 1982.

Maalderink, P. G. M. De Militaire Willems-Orde sedert 1940 [The Military Order of William since 1940]. Houten, Netherlands: De Haan, Unieboek BV, 1987.

Neumann, H. and E. Van Witsen. De Sumatra Spoorweg [The Sumatra Railway]. 2d ed. Middelie, Netherlands: Studio Pieter Mulier, 1985. The Sumatra Railway. Translated from the Dutch by S. D. Ten Brink. Middelie, 1982.

Nortier, J. J. Articles related to the Japanese landing and advance in Middle and North Sumatra. Stabelan, March and June 1994.

Scholten, KNIL Major General P. Op reis met de “Special Party” [On the Road with the “Special Party”]. Leiden, Netherlands: A. W. Slijthoff, 1971.

Van den Bos, H. Vrouwenkampen Padang en Bangkinang (Sumatra’s Westkust) 1942-1945, Deel II [Report: Women’s Camps Padang and Bangkinang (Sumatra’s West Coast) 1942-1945, Volume II]. Zoetermeer: self-published, 1998.

Van den Bos, H., editor. Verslag: Vrouwenkampen Padang en Bangkinang (Sumatra’s Westkust) 1942-1945, Deel I [Report: Women’s Camps Padang and Bangkinang (Sumatra’s West Coast) 1942-1945, Volume I]. Zoetermeer, Netherlands: selfpublished, 1989.

Van Heekeren, C., et al, eds. De Atjeh-party [The Aceh Party]. The Hague: Bert Bakker / Daamen NV, 1966.

Van Heerkeren, C. et al, eds. Het pannetje van Oliemans; vijfhonderd krijgsgevangenen onder de Japanners [The Oliemans Mess Kit: Five Hundred POWs under the Japanese]. Franeker, Netherlands: T. Wever, 1975.