Bastiaan “Bart” M. Drees, January 1, 2017

Old men. Ever since I can remember, I have had an affinity for old men. My grandfather, Herman Meijer Drees, was the first to show me his wisdom, talent, and dexterity. I have early memories of visiting my oma and opa in the Netherlands, before I was 6 years old. Opa took me to his work room in the basement of their apartment building where he had a shop. He was carefully fixing some delicate wooden object, perhaps a picture frame. He used very small nails and the lightest touch of the hammer. When he concentrated hard, he always had his tongue sticking out between his teeth. His hands were wrinkled, compared to mine. He had patience and did meticulous work. Later, after my family immigrated to Dallas, Texas, he came to stay with us when I was seven. There, he took it upon himself to repair an antique barometer that contained a long, U-shaped glass tube full of mercury that needed to be replaced after the move. Again, he had the patience, dexterity, and confidence to make the repairs successfully.

My opa may have been the first old man to gain my respect, but he wasn’t the last. Looking back on my life now, I treasure having met and worked with people like Dr. James Borrer at the Ohio State University, the first author of a classic entomology text book, Borror, Delong, and Triplehorn’s, Introduction to the Study of Insects (usually referred to by students as “boring, too long, and triple boring”). I worked in his laboratory where he managed the largest bioacoustics library of animal sound recordings. He made long-playing (LP) records which he sold commercially as his retirement project. He was an old, crusty fellow that chain smoked in his laboratory in the late 1970s. For my dissertation researching horse and deer fly (Diptera: Tabanidae) sounds, I worked in Don Johnson’s laboratory where I met Dr. George Wharton, the “father of acarology” (the study of mites and ticks). He was working on a parasite of the red imported fire ant, the “straw itch mite”. It was the first time I would see a laboratory colony of this major invasive exotic pest ant that would later consume much of my career as an entomologist at Texas A&M University. There is truly wisdom that comes with age, and I was awed. Now I am 64 years old and blessed with a 2-year-old grandson. I hope I can instill that type of awe in him as he grows up.

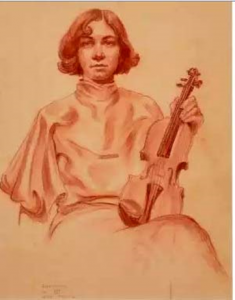

When I was in high school, my parents found a local artist, Olin Travis, who gave private art lessons in his home. His wife, Josephine, played violin in the Dallas Symphony Orchestra where my cello teacher, Mr. Herscowitz, also played. Every Saturday, Mom would either drop me off, or I would drive myself after my parents bought my brother, sister and me a Volkswagon Beetle to share (This sharing did not go too well and resulted in huge fights between Herman, Frieda and me.

One weekend, about a month after I got my driver’s license, I was heading to my lesson and decided to cut across a parking lot to avoid waiting at a red stoplight. The parking lot exit was on a steep ramp. There were two women walking down the sidewalk who decided to walk behind my car. The beetle had a stick shift that I was still learning to use well. That meant you had to give the car gas while lifting up on the clutch to keep from rolling backwards on an incline. I was so preoccupied looking back and working the peddles that I pulled into the street without looking for traffic. I was hit in the front left fender by a brand new, green Ford Mustang! My door sprang open, and I hit the cement in a sitting position. My car was pushed back into the parking lot by the impact, but it was still running and heading for the stores’ plate glass windows. I sprang up and ran after my still-moving car, hopped in, and pulled the emergency break. A policeman was there in just seconds. He got out of his patrol car laughing hysterically, saying “I’ve never seen anyone knocked out of their car and then have to run after it like that!” Wonderful.

My lessons with Mr. Travis were an inspiration and a real learning experience for me. I treasure his approach to education even today. For starters, when I took my first lessons he explained that his job was not to tell me what to draw or paint. I was to bring him my ideas of what I wanted to express. His job, he said, was to give me lessons on HOW I could best present my ideas using different media, styles’ and approaches to make the best presentation of those ideas possible. Of course, during the lessons, his students (often there were two students taking lessons together) also sketched and painted still life scenes and did other exercises to help improve our skills.

One of his “rules” was to never give your artwork away. He had had a career as a locally well-known professional artist in the Dallas area during the Great Depression. Now retired, but still teaching young students, he told me stories about being out of money and having to live in a tent during those times. He gave a lithograph print to each of his students. He gave me a print of a beautifully rendered black woman’s portrait in a ¾ view. It was embossed with his unique signature stamp. I brought it home, but it was too big and too valuable to leave lying around the house. I searched and searched for a place to put it, finally deciding on a large book under my parent’s coffee table where it remained. Much later when I was home from college, I tried to find it. The safe place had become too safe. I never found it again, and have continued looking in every large book in my parents’ home until they both passed away and we emptied their home (the lake house) of all possessions.

I learned a lot about art and being an artist from Mr. Travis. He taught me about using oil paints mixed in melted bee’s wax that instantly dried when applied to a canvas, making a deep pile texture on the surface. He used linseed oils and varnishes to give canvases a shiny finish. His canvases were often Masonite boards primed with Gesso, a white under paint layer. He applied paints using tools other than a paint brush, like a pallet knife or a crumpled-up paper towel. And, he imparted a lot of “rules” to creating, including:

- Never allow a line in your composition to go to the corner of the canvas because that directs viewers to leave the picture. Be aware of the lines and proportions, like the golden rectangle, in the composition.

- Do not use more than one technique in a picture to avoid the contradiction of styles.

- Avoid using cross hatching in illustrations to cover up basic design flaws in the art work.

Later, when I took upper division art courses (including etching, nude figure drawing, sculpture, acrylic painting and silk screening) as electives to finish out my core curriculum in biology at West Virginia University, I learned from my teachers there that new rules applied, and many of Olin Travis’ rules were out-of-date. For instance, in acrylic painting classes, the teacher advocated “anchoring” the graphic lines of the artwork to the corners of the canvas. Also, he insisted that “illustrations” were not really art, much like scientists who separate “basic” from “applied” forms of research.

Mr. Travis owned a black and white, classic Chevrolet station wagon. During one of my lessons in my senior year in high school, Mr. Travis took me and another student on a field trip down the street to a park on White Rock Lake. He was old at the time (1970), and he drove very, very slowly. I wondered whether we would arrive safely. I did my best drawing the landscape, but had a really, really hard time concentrating. I did not know how to tell an elderly person that the time for driving a car may be limited by age without hurting his feelings.

When I graduated from high school in May 1970, I immediately started summer school in West Virginia University. I never went back to touch base with Mr. Travis and understand that he passed away in 1975. His artwork lives on; just Google search for “Olin Travis” and marvel at what shows up! That’s the thing about being creative and producing any type of art (including music, poetry, stories, photographs, drawings, paintings, sculptures, ceramics, wood working, taxidermy, and recordings): they live on after the artist dies. If the artist is lucky, the products of their talent(s), time, labor and love do not end up in the trash, but live on. In that way, they provide a form of immortality to the creative artist. That’s what the artist lives for and what motivates them at some level.