Bastiaan “Bart” M. Drees, July 27, 2016

I’m hesitant to write this anecdote because I’m not proud of the outcome; however, it is something I often think about as we all impact the world around us. I’ve been collecting butterflies since my family immigrated to the U.S.A. in 1959 when I was 6 years old. I’ve just had an inexplicable fascination with them. I remember catching Hackberry butterflies in the back alley of our first rented home on Mimosa Avenue in Dallas, TX in the spring of that year, the Pittosporum bushes were in flower with the strong, sweet-sick odor of the flower clusters. Later, after my family moved to Stichter Avenue, I was collecting swallowtail butterflies in our backyard during the summer – clad in an American Indian outfit my Mom helped me make. Not knowing anything about collecting butterflies or preserving them, I would put the live specimens in jars and watch them beat their wings into ragged edges, losing all of their scales and coloration. I did this until my parents finally gave me my first entomology book by Wigglesworth (1964).

In high school, after I got my driver’s license, I would drive to a nearby undeveloped area we called “the mountains” and continue to collect butterflies and other insects. I remember thinking to myself during these hot Texas summer afternoons “Why am I doing this? What is the purpose? What will this lead to?” I fashioned boxes with glass tops in my garage and began an insect collection that I kept under my bed. Even my closest neighborhood friends did not know I had them. It was so un-cool to have an interest in bugs as a teenager. I still have some of those specimens today, more than 45 years later. Little did I realize that one could make a living studying insects as a paid profession!

I left home in the summer of 1970 for college. In my sophomore year, my neighborhood friend, Mike Flanery, joined me at West Virginia University in Morgantown, WV. I was enrolled in a pre-med program at that time. My parents wanted me to follow in the footsteps of my uncle, Johan “Joop” Vaandrager, my mother’s youngest brother. Joop, incidentally, had been born and grew up in Indonesia (Dutch East Indies). As a child, he was an avid butterfly collector and had a nice collection. Unfortunately, when World War II broke out, the Japanese army overtook that country and sent my uncle to prison camp where he remained until the end of the war. The Japanese took his insect collection and almost all other family possessions (Note: When he got out of prison camp at the age of 17, he weighed 75 pounds, having survived by eating wild hot peppers growing on prison grounds. He went on to become a general practitioner in Garland, TX, for many years).

Anyway, I was barely passing my early college classes – particularly chemistry. My goal was mainly to stay out of the Viet Nam war draft with a student deferment. My lottery number, drawn by the Army to pick who would be drafted first, was low. My chances of getting into med school were close to zero. About that time (sophomore year), I took my first entomology course as a core elective. It was offered in the Forestry Department, not the Biology and Zoology Department where I had taken my required pre-med biology courses so I had been unaware of it. Dr. Linda Butler was the young professor who taught the course. I had found my heaven! I aced the course and realized how much this topic still grabbed my attention.

Mike and I soon began going on insect collecting trips for fun and not worrying about whether it was “cool” or not. On one spring break, we went camping in Big Bend National Park, and secretly (illegally and unsuccessfully) tried to collect butterflies when we felt like we were all alone. That’s the first time I saw a California Sister butterfly! Sitting on a mountain ledge overlooking the park, I came to the decision to try to get into graduate school for Entomology and “come out of the closet” as a proud entomologist!

Back in West Virginia, Mike and I would drive the countryside around Morgantown on weekends, looking for butterflies to collect. We soon discovered a field where Zebra swallowtails flew in abundance around a patch of their host plants, pawpaw trees. We collected other swallowtail butterflies from wild flowers and from around puddles where butterflies sip moisture on hot summer days. Mike helped me get to know the common and scientific names of common species, being much more of a reader than I had ever been. It was the first time I remember thinking that learning could actually be fun! I will always be indebted to Mike for helping me gain confidence in my career choice.

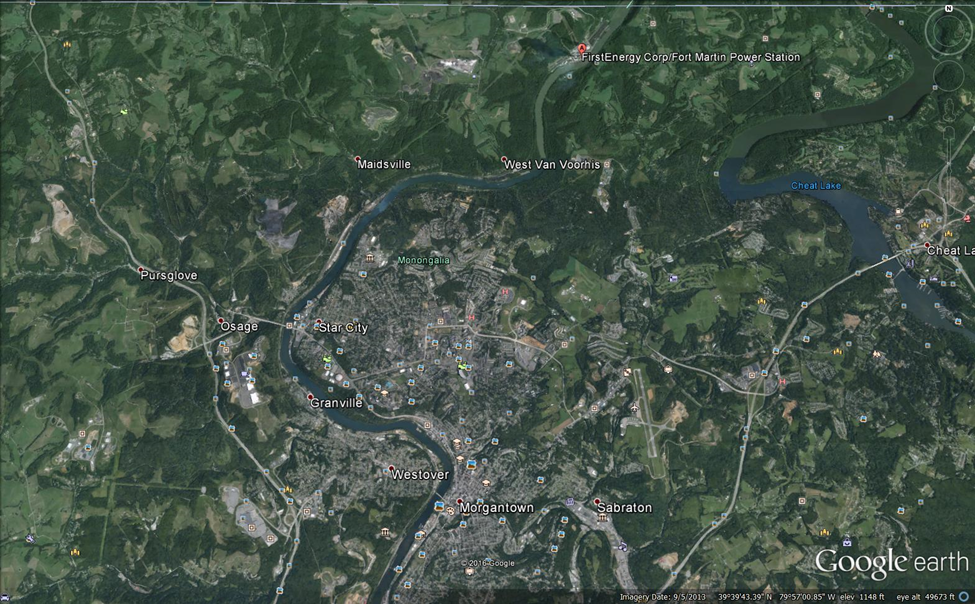

One day, we happened upon a pasture adjacent to the Fort Martin power plant north of Morgantown, Monongalia Co., near the Pennsylvania state line. We spotted some large butterflies with their slow, sailing flight over the field and stopped the car at the side of the road to begin collecting. The butterflies were huge and beautifully colored. We had no idea what they were, but knew we had never seen them before. We collected a series on July 20,1973. Back in my apartment, we looked up the species in my copy of A Field Guide to the Butterflies by Klots (1951), to find out that they were the Regal Fritillary, Speyeria idalia, described in 1773 by Drury (Note: I went back on Aug. 13, 1978 to collect another series).

My first scientific journal article was co-authored by my major advisor and mentor, Dr. Linda Butler in 1978, entitled “Rhopalocera of West Virginia” and published in the Journal of the Lepidopterists Society, Volume 32, Number 3, pages:198-206 (Note: Rhopalocera means butterflies, as a Insecta sub-order, Lepidoptera, which also includes moths). It included the listing of Speyeria idalia from Monongalia County – perhaps as a county record!

Nearly 20 years later, my friend, Thomas “Tom” J. Allen, in his book, The Butterflies of West Virginia and Their Caterpillars (University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburg, PA, 1997, 88 pages) wrote:

Description: Wingspan is 2 5/8 to 3 5/8 inches (66-92 mm). The Regal Fritillary is a large spectacular butterfly, as beautiful and different as the Diana (Speyeria diana).

Distribution: The Regal Fritillary has been rapidly disappearing from its eastern range. Western populations are more stable than those east of the Mississippi River. Although it has been reported from several counties in West Virginia, most of these records have resulted from temporary populations now extinct. The most recently known population occurred in northern Monongalia County, and it, too, has been threatened by habitat loss. Other isolated populations are possible in local areas where suitable habitat (and their wild host plants, violets) is found, but recent surveys indicate that this species has probably disappeared from West Virginia.

(http://lepidopteraresources.homestead.com/Speyeriaidalia.html)

http://www.learnaboutbutterflies.com/North%20America%20-%20Speyeria%20idalia.htm

I have enjoyed a 33 year-long career at Texas A&M University and continue to enjoy entomology as a hobby. I have produced a number of single and double glass frames displaying butterfly specimens from around the world – both ones I have collected and ones I have purchased on line from E-Bay and other sources. I have developed and delivered a number of talks and Extension handouts on butterfly gardening and butterfly appreciation and continue to believe that collecting and curating insect specimens for display is the best way to study and learn about them. However, my experience with collecting the last Regal Fritillaries in West Virginia has reminded me of the unintended consequences our actions may have on this planet and its inhabitants. Whether it was over-collecting of a very restricted population or loss of habitat that led to their disappearance, it really doesn’t matter. They are now gone forever – at least in West Virginia. I may bear some responsibility for that, and if so, I am truly sorry.

______________

Klots, A. B.1951. A Field Guide to the Butterflies. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, MA.349 pages.

Wigglesworth, V. B. 1964. The Life of Insects. The New American Library, Inc., New York. 383 pages.